Volume 1, numéro 1 – 2019 : La responsabilité sociale des organisations et entreprises en Afrique francophone

An assessment of participatory management of forest resources by communities neighbouring the mount Cameroon forest reserve

TASSAH Ivo TAWE et ATEMKENG Andre NDAH

The success or failure to manage conflicts arising from the exploitation of natural resources is determined by changes through a sequence of historical events and the rights of indigenous communities in natural resources management (Ngwasiri, 2001). The colonization experience of African States brought severe socio-economic and political challenges resulting from rules and policies instituted by colonial powers. In Cameroon, the divide-and-rule policy of colonial powers was expressed through indirect rule of the former British Southern Cameroons, assimilation and “association” with French Cameroon contributed significantly in distorting the ways in which “indigenous” traditional Cameroonian communities handled natural resources management. This resulted in conflicts. According to studies by Ngwasiri (2001), the colonial policies of natural resources management were intended to guarantee the regular supply of agricultural and forestry resources to Europe. These policies generated conflicts and smouldering hostilities from the indigenous populations as exemplified by the Bakweri land problem (Ngwasiri 1995; Tumnde 2001; Mbuagbaw and Lambi 2003).

After independence, the national land laws in Cameroon were developed using the German concept of herrenlos land, which means land without an occupant, which is declared as crown land vested in the German Empire. According to Tamasang (2019), the public trust theory of natural resource management requires that the State hold natural or environmental resources in trust for the benefit of the public and is not subject to private ownership. Since 1974, Ordinance No. 74-1 designated the Cameroon government as the custodian of all land within the Cameroonian territory. In this framework, the state has the legal responsibility to ensure the well-being of its citizens through the rational and efficient use of land and its resources.

Contemporary dynamics in the exploitation and use of natural resources requires sustainability measures to curb the challenges of global warming – a concept that is rooted in the Rio Conference of 1992 and the Paris Agreement of 2015 on climate change. Looking forward, the sustainable exploitation of natural resources requires that countries prioritize Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which must take into consideration the rights of indigenous communities whose livelihoods depend on the sustainability of these resources.

The rights of indigenous people in the management of natural resources becomes complex in Cameroon given that the question of who is an indigenous person is debated. According to studies by Mbarga (2019), there is no internationally accepted definition of the term indigenous peoples. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples adopted by the General Assembly on the 13th of September 2007 does not define the term, on the premise that, there is no comprehensive definition that encompasses the diversity of cultures and history of indigenous peoples in the world. In order to address this question, Mbarga (2019) noted that the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights observed all Africans as indigenous, predicated on the premise that they have always lived in the territory. Based on this supposition, the exploitation and use of natural resources becomes a fundamental right for all Africans.

According to Mouangue Bonam Kobila, (2009), the view of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights on indigenous populations has been greeted with fanfare in the preamble of Cameroon’s constitutions. This document recognizes the existence of indigenous people in all the ten regions of the country by stating that all people are indigenous to their land. This assertion therefore makes it difficult for the effective management and sustainable use of natural resources in Cameroon. This is particularly true in the case of the Mount Cameroon forest reserve where the constitution gives legal rights for all Cameroonians to settle anywhere within the national territory.

Cameroon’s protection of forest resources and the mechanisms to share benefits of forests among neighbouring communities requires us to ask the question: “who is an indigenous person within the community?” The politics of recognition among communities adjacent to the Mount Cameroon forest reserve has resulted in the expression, “came no go, graffee .” This view has deprived some of the locals adjacent to the forest resources from royalties, making it difficult to claim effective management of the forest. These shortcomings have compounded implications on climate change mitigation, with particular mention of the Mount Cameroon forest reserve in Buea Subdivision.

Despite several studies, the success of Cameroon Forestry policy to conserve this area has been limited in resolving forest exploitation and creating alternative income-generating activities. This could be attributed to the fact that Government and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have paid very little attention to the mechanisms of benefit sharing within local communities that ensure effective participation. This has made it difficult for the effective implementation of policies and management of the forest to the detriment of climate change mitigation. In this context, the Mt. Cameroon forest area remains prone to fire damage, illegal poaching and exploitation of Timber and Non-timber Forest Products (NTFPs). According to the 2010 – 2020 Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (GESP), despite the increase in protected forest areas, between 2001 and 2008 the rate of environmental degradation increased by 82%. This situation is largely the result of an increase in the population of non-natives whose livelihoods depend on the Mount Cameroon forest reserve.

Context

The natural forest environment has falsely been considered by many as an unlimited reserve of wealth (Tassah, 2018) and this is the reason why humanity continues to exploit it for food and their livelihood. This has resulted in unintended negative effects on the natural ecosystems and the environment and a corresponding decrease in the products and services provided. Increased deforestation and land degradation has led to loss of water drainage basins, destruction of habitat for species including monkeys and birds, while increasing soil erosion, loss of soil nutrients and disruption in natural climatic cycles. The implications have been a fall in agricultural productivity and the extinction of some flora species like Prunus Africana, cola suboppositifolia, Mbibabdon and fauna such as drill, preuss monkey, and Mt. Cameroon Speirops (FAO, 1999, FAO, 2001a). Sustainable resource management is important because communities depend on them for food and subsistence.

This challenge places human at a defining moment in history, where we must trace our origin, culture and indigenous knowledge in relation to the environment. Mountain forests hold key resources including their recreational importance to humans and the ecological services. They are essential to the resilience in a rapidly changing global ecosystem. This is particularly important when addressing climate change. Human populations face widespread poverty and loss of indigenous knowledge among mountain inhabitants. As a result, most global mountain areas are experiencing rapid environmental degradation, reducing their potentials to mitigate global climate change by absorbing carbon through photosynthesis. According to the African Journal of Plant Sciences, about 10% of the world’s population depends on mountain resources for food and medicinal products. A much larger percentage draws on other mountain resources including honey, fodder, and charcoal. Special emphasis should be placed on water. As mountains remain a sanctuary for biological diversity and many endangered species, the proper management of mountain forest resources and the socio-economic development of mountain communities requires urgent attention.

Mountain areas accommodate a large diversity of ecological systems. There is, however, very limited knowledge on mountain forest ecosystems as these resources feed, treats, educates (through indigenous knowledge) and clothes communities. They also provide humans with housing, medicines and spiritual nourishment. The current decline in biodiversity is largely the result of human activities and represents a serious threat to human development. Despite mounting efforts over the past years, trends in loss of the world’s biological diversity continue. This is mainly due to habitat destruction for medicinal and food purposes, over-harvesting, consumption, and pollution due to clear cut forestry for agriculture. This threatens forest resources that constitute a capital asset with great potential for yielding sustainable benefits (AGENDA21, 1992). According to studies by FAO (1995), forests and trees have an important role to play in poverty reduction and the stabilization of the natural climatic cycles. Humanity exploits forests for timber and other non-timber products. It is important to underline that forest in the past have been the main source of subsistence for communities living in or near them. They depended on the forest for basic goods including food, shelter, healthcare, clothing, energy and a source of income (Okafor, 1995; 1998; Kabuye, 1998; Neumann, 2000 and FAO, 2001b).

We must keep in mind that poverty remains a complex, multidimensional problem which originates from both the local and national domains. The eradication of poverty and hunger, greater equity in income distribution and human resource development constitute major challenges everywhere. This is one of the major reasons why it is important to understand how people reliant on the forest can make a living (AGENDA 21, 1992).

Poverty and environmental degradation are closely interrelated. While poverty results in environmental stress, the major cause of continued deterioration of the global environment and forest destruction has been unsustainable patterns of human consumerism. Therefore, the efficient use of forest resources should be consistent with the goal of minimizing depletion, reducing pollution and modifying trends of consumerism. In order to meet the challenges of the environment and development, states decided to establish a New Global Partnership (NGP). This partnership commits all states to engage in a continuous and constructive dialogue on conserving forest resources that increases their capacity as carbon sinks and improved biodiversity protection. This view is inspired by the need to achieve a more efficient and more equitable world economy (I U N, 1994). It is for these reasons that the management of forest resources has risen to the top of the global political agenda with an increasing presence of institutions. In our study, this includes the World Bank, the World Conservation Union, World Resources Institute, World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF), the Mount Cameroon National Park (MCNP), German–Cameroon Cooperation (GIZ), Environmental Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF), Green Cameroon, Pro Climate International and the Mount Cameroon Ecotourism Organization (Mt.CEO). These organizations usage of Mt. Cameroon National Park (MCNP) in the South West Region of Cameroon is vital for launching programs contributing to the sustainable development of mountain ecosystems in the Buea Subdivision.

Cameroon is endowed with both a variety and abundance of living organisms, which is referred to as biodiversity. The rapid degradation of forest resources for food and traditional medicine has become a central concern with natural and social scientists (WWF and IUCN, 1994, Mboh, 2001). The exact rate of forest resources loss in the Mt. Cameroon Area through animal, natural plant consumption and overexploitation at the local, national and international level is unknown, but its direct causes include:

- Unsustainable agricultural practice and excessive hunting of animals for food by the local communities around the slopes of Mt. Cameroon

- Overexploitation of natural resources, like Prunus Africana for traditional medicine

- Climate change and the introduction of alien species which can be attributed to uncontrolled landscape changes

- Expansion of urban areas for development

- Human population growth

- Economic decline and hardship due to the increasing poverty levels.

Forest resource management forms the basis of the global life support system, within which humans have traditionally fulfilled many of their needs by taking advantage of the resources and species within a balanced ecosystem. Many plant species such as Prunus Africana, Cola suboppositifolia in the Mountain area have historically supply crucial food and medicinal supplies. Buea Subdivision is an excellent example of improvements in diversity. The demographic shift in its population is attributed to the continued economic immigration of non-natives for diverse activities, which are most often for economic and agricultural purposes. Mt. Cameroon population growth can be attributed to income-generating activities from its rich black volcanic soil, vast rain forest, riveting volcanic craters, diverse plants species for traditional medicine and animals for food. Inhabitants rely on these attributes for their livelihood (Mt.CEO, 2010). Degradation, over consumption and over exploitation of the forest resources have made the management and conservation since the beginning of the 1990s a principal objective of local, national, and international conservation organizations.

Forest resource management is a crucial issue in today’s world to resolve environmental degradation and forest destruction. The earth depends on the natural environment for its survival. The forest provides a multiplicity of functions that support the socio-cultural as well as the economic benefits (Ekane 2000). For example, the forest provides agricultural and medicinal products. Cameroon is endowed with a diversity of natural resources that supports 70% of the population in the primary sector of the economy (Neba 1997). With an estimated population growth rate of 2.6% (World Fact Book, 2013), one will definitely expect these forest resources to come under increasing pressure in conjunction with poverty and economic hardship (World Bank Development Report, 1992). Human activities affect the environment and forest resources in a number of ways through indiscriminate exploitation that results in the destruction of habitat, endangered plants and animal species. The tropical forest of Cameroon is a victim of this calamity (Lambi, 2001).

The broadened scope of environmental management should involve all stakeholders: governments, indigenous communities, NGOs and Common Initiative Groups in the Mt. Cameroon forest conservation program. This study sets out to explore mechanisms and strategies for sustainable forest management. It is important to integrate the local communities in the management process. This provides sustainable mechanisms to share forest royalties, which encourage efficient management and ensure climate change mitigation.

Research site

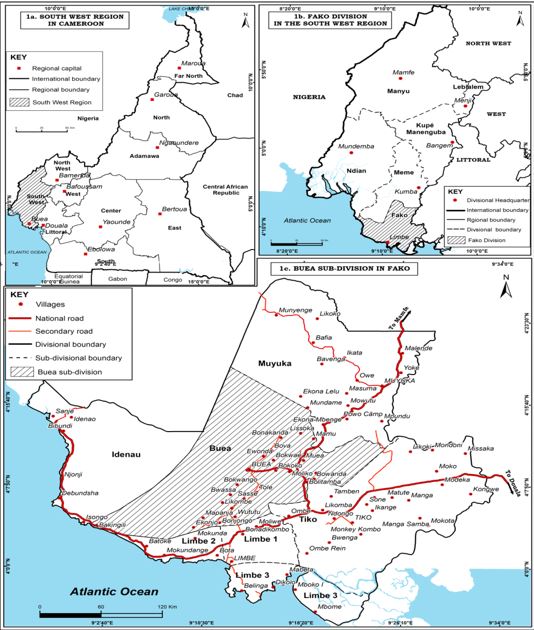

Mt. Cameroon located close to the Atlantic coast is found in the South West Region of Cameroon. It is the highest mountain in West and Central Africa with a height of 4,100 m above sea level. The mountain forms part of a volcanic chain known as the Cameroon volcanic line (Ekane 2000). The area is volcanically active with young volcanic soils which are rich in nutrients. Since the colonial epoch in the 19th century, moderate explosive and effusive eruptions have been recorded from both the summit and flank vents. Recorded events include 1902, 1922, 1949,1959,1982,1999 and 2000. During the most recent eruptions, lava flow burnt and destroyed the forests, killing some species of wildlife and flora which were already declared endangered in the region. The proximity of this region to the Atlantic Ocean provides a favourable climate as a result of orographic rainfall. Rainfall occurs mostly on the windward side of the slope, which has a very high mean annual rainfall of approximately 10,617 mm/year near Debundscha. A short dry season occurs between December and February; the humidity remains high at about 75-80%. The rainfall gradient and large variation of climate conditions around the mountain influence vegetation species and plant growth. The unbroken sequence of vegetation characteristics from evergreen forest close to the sea level to the sub-alpine vegetation near the summit makes Mount Cameroon unique in West Africa. The high levels of biodiversity are internationally recognized with at least 42 plant species and two bird species native to the area. There are also three species of endangered primates and a small population of elephants (MCNP, 2014). The area is also extremely rich in fauna diversity. As a result of this tremendous biodiversity, in 1994 Mt. Cameroon was listed as a centre of plant diversity by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Map 1 indicates the location of Buea in the South West Region of Cameroon.

Map 1. Location of Buea in the South West Region of Cameroon

Source: Wani et al. (2017)

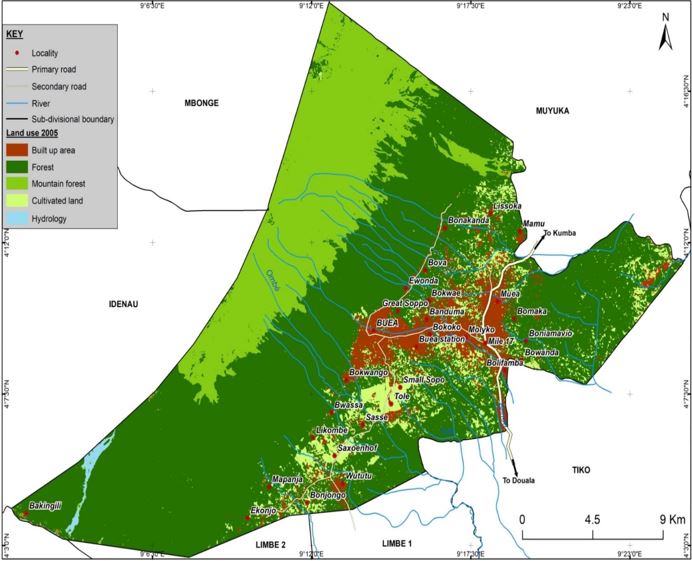

The socio-economic activities in this area include agriculture, hunting, illegal wildlife harvesting and touristic activities. Both subsistence and commercial farming dominate this area. It is an area of economic importance in Cameroon. Hunting is another important activity for household consumption and commercial purposes. The area is a very important tourist destination, with many touristic attractions that include historical monuments including the Prime Minister’s Lodge and other remnants of German colonization in Buea (former German capital). A rich biodiversity instrumented a botanic and zoological garden located in Limbe. Although the indigenous Bakweris are outnumbered by regional Cameroon migrant workers recruited for the plantations, they contribute to a very rich culture. Cultural diversity also plays an indirect role in natural resource management in the area. The population of 300,000 inhabitants is made up of indigenous Bakweri, Bomboko, Balundu and Bimbia tribes (Buea Council Report, 2018). In January 2009, the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife created Mt. Cameroon National Park to improve the protection of wildlife and other flora in the region by enabling NGOs at local, national and international levels to assist in protecting the natural resources for a sustainable environment. Due to over-exploitation and excessive hunting of forest plants and animals for consumption at the local levels, forest resources are quickly disappearing. This, coupled with the climatic consequences of forest conversion for agricultural purposes, is accelerating environmental pollution and global warming. On the other hand, the intervention of NGOs alongside the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife in conserving and protecting the Mt. Cameroon National Park Forest resources has reduced the rate of consumption and exploitation of forest resources. Climatic change mitigation has been addressed through policy on forest conversion for agricultural purposes; a measure that has contributed to the conservation of the forest for sustainable livelihood and to some extent, ensuring a balance in the global ecosystem. Unfortunately, for the local populations continued poverty and economic hardship, the State and International Organizations to turn a blind eye to these policies measures. Figure 2 is a map of the Mt Cameroon area showing communities adjacent the mount Cameroon forest and the current trends of forest degradation.

Map 2. Map showing LANDSAT Image for Mount Cameroon Forest Reserve and communities adjacent the forest indicating current trends in forest invasion

Methodology

Research Sample and Data Collection

After defining the population, elements were selected to provide the required information using primary and secondary data. In order to collect this data, a household-based survey was sampled using a cluster approach. Four communities adjacent to the forest reserve were used in the study; namely, Buea Town, Likoko-Membea, Bokwango and Bonakanda. Interview guides were produced and administered to the following groups: local authorities, local council, NGOs and local community leaders. Only persons aged 15 and above were sampled for the study. The reason is that this was the age observed to be actively involved in forest exploitation, alongside that they this age and above are expected to have acceptable judgment. The population-based survey was carried out to sample individual members of the communities. These communities were selected using simple random sampling where the names were written on pieces of paper and the targeted number of communities drawn at random. The sample was stratified because the appreciation of authorities, traditional authorities, local population and Civil Society Organizations were very vital in the forest management concern. Each of these groups composing a stratum.

Data was collected using two (2) methods; primary and secondary. Primary data was gathered from fieldwork through interviews, key informants with the help of a questionnaire, focused group discussion and observations of the studied population(s). Secondary sources include, reviewing published documents and books.

Data Entry and Analysis

Open-ended questions were analyzed using the process of thematic analysis whereby concepts or ideas were grouped under umbrella terms or key words. As for the quantitative data, a pre-designed EpiData Version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense Denmark, 2008) database was used to enter the data with in-built consistency and validation checks. Further consistency, data range and validation checks were performed in SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Inc., 2012) to identify invalid codes. Data was made essentially of categorical variables and analyzed using frequency, proportions and Multiple Responses Analysis to ground concepts that emerged from open-ended questions. Reliability tests were performed to assess the internal consistency of responses using Cronbach Alpha reliability analysis coupled with the inter-item correlation test. Chi-Square test of equality of proportion was used to compare proportions for significant difference. Relationships between conceptual components were assessed using Spearman’s Rho correlation test. Data was presented using frequency tables, charts and conceptual diagram. All statistics were presented at the 95% Confidence Level (CL), Alpha =0.05.

Presentation of results

Profile of Respondents

Both sexes were well represented in the sample; there were 92 (55.8%) male and 73 (44.2%) female respondents. A close look at these proportions indicates that males in all the communities tend to dominate in the exploitation and farming activities. Respondents reported that the women in the areas tend to migrate into the towns in search of other livelihoods, leaving the agricultural sector in the villages to the males. It was reported, however, that the proportion of women in the gathering of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) outnumber that of the males who were more involved in farming and hunting. The population was observed to be relatively young, with 88 (53.3%) between 15-30 years, 47 (18.5%) aged 31-45, and 30 (18.2%) aged 46 and above.

The age group of 15-30 years was observed to be the most active and it is this age group that is most involved in agriculture and illegal forest resource exploitation and poaching, followed by the 31-45 year range. The age group of 46 constitutes the aged that are more dependent on the active group (15-30) for their livelihood needs. Out of the 165 participants, 88 (53.3%) were married, 66 (40.0%) were single, 4 (2.4%) were widowed and 7 (4.2%) were divorced. Considering those that were married, the relative rate of divorce could be (7/99)*100=7.1%. Among those who were married, more males were household heads, with a proportion of 35 (61.4%) as against 10 (32.3%) for the female. It was observed that the ratio of men household heads was significantly higher (χ2-test: χ2=4,185, P=0.041) among the non-indigenes, with weight of 9 (90.0%) as against 26 (55.3%) for the indigenes. Therefore, the proportions of the non-indigenes who rely on the forest products are more than the real indigenes (Bakwerians). The population around the forest reserve was observed to be dominantly Christian with 132 (80.0%) while 32 (19.4%) practised Ancestral/Traditional religion and 1 (0.6%) were Muslim. This is so because the Catholic, Presbyterian, Baptist and Pentecostal were the dominant churches found in the four communities. Farmers and skilled workers were highly represented, with a weight of 30 (18.2%). Other occupations included hunting 9 (5.5%), fishing 1 (0.6%), semi and unskilled labour 13 (7.9%), retired 7 (4.2%), applicants 15 (9.1%), housekeeping 14 (8.5%) and studying 46 (27.9%).

The population around the forest reserve was highly diversified, coming from 16 different Divisions and 21 Ethnic Groups. 106 (64.2%) participants were indigenes and 59 (35.8%) non-indigenes. A greater proportion of the respondents were Bakweris 106 (64.2%) from Fako Division, 107 (64.8%) who are the indigenes of Buea Subdivision, referred to as “Bakweris of the Mountain.”

Households were relatively large, with only 51 (30.9%) of them having 3 persons and below, while 64 (38.8%) had 4-6 people and 50 (30.3%) 7 and above. The population was generally monogamous, 82 (88.2%) as against 11 (1.8%) polygamous. However, some respondents could not determine their marital status. This is because some women who are married were confused or did not know under which marital status they belonged.

Income levels were relatively low, with 71 (43.0%) earning less than 30.000FCFA, 67 (40.6%) 30.000-100.000 FCFA and only 27 (16.4%) earning above 100.000FCFA. As concerned the distance from the forest, 69 (41.8%) of the participants estimated their distance from the forest to be less than 5Km, and 96 (58.2%) 6-10 km. It was observed that the closer the distance of the community to the forest, the more likely participation in illegal exploitation and poaching of the forest resources. Therefore, communities nearer to the forest (41.8%) were observed to be highly engaged in the massive exploitation of the forest resources without considerations to the restrictions of state permits under Cameroon’s 1994 Forestry Laws.

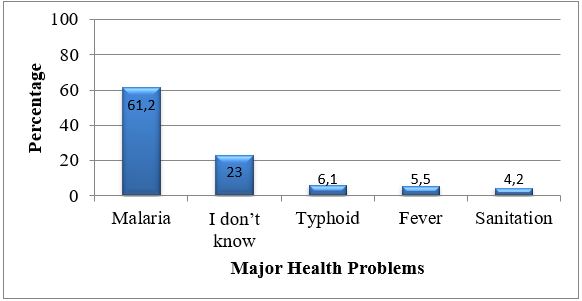

Major Health Problems

The major health problem mentioned in communities was malaria 101 (61.2%) as a result of proximity to the forest. This was an also an indicator of exposure to unfavourable climatic conditions, unsustainable environment, pollution in various ways, poor environmental waste management. Figure 1 indicates the various health problems faced by the respondents adjacent the Mount Cameroon Forest Reserve.

Figure 1. Distribution of Major Health Problems in the Communities (N=165)

As indicated in Figure 1, ill health was also linked to poverty and environmental degradation. It was observed that the rural poor were forced to rely on the forest to improve health conditions. The population pressure on the fragile resource base for medicinal purposes as is the case with Prunus African in the Mt. Cameroon forest area in Buea Subdivision has paved the way for deforestation and environmental degradation with implications on programs of climate change mitigation. Medicinal plants are of critical importance, especially in poor communities where cheap western medicines are prohibitively expensive. Culturally, these plants also play an important economic role. The bark, leaves and roots are traditionally used either alone or in association with other ingredients to tackle a number of ailments including malaria, typhoid (Figure 1), chest infections, stomach ache, rheumatism and gonorrhea.

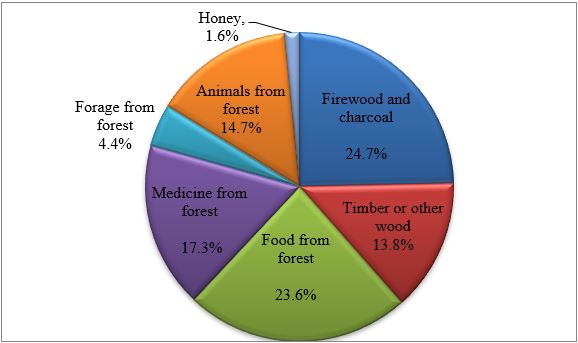

Forest Resources Economic Contribution

Figure 2. Products exploited from the forest by community members (N=165)

Projections of Figure 2 indicate that the most exploited resource from the forest is firewood and charcoal (24.7%), followed by forest food (23.6%), medicine (17.3%), animals (14.7%), timber or other wood (13.8%), forage (4.4%) and honey (1.6%). The forest is a resource for forest products and income generation to improve living standards. The forest also provides the communities with Timber and Non-Timber products and some class “C” animals as food including vegetables, pears, fruits, plantain and cocoyam that alleviate poverty and improve on their living standard. Also, it is an environment where a cultural of ritual sacrifices and the pouring of libations are commonly carried out for the protection of the community. Therefore, these communities have developed deep relationships of dependency on the forest for livelihood, since forest resources contribute to maintaining their livelihoods conditions.

Alternative Income Generating Activities

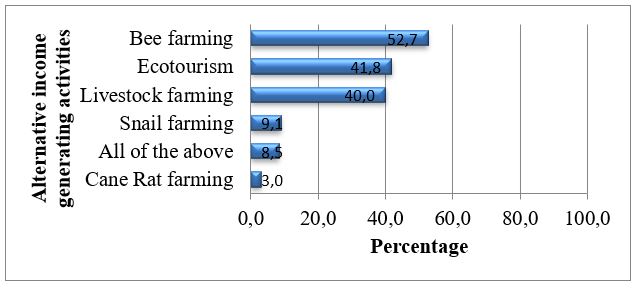

Figure 3 illustrates the principal alternative income-generating activities. These activities include bee farming (52.7%), ecotourism (41.8%) and livestock farming (40.0%). Among others were snail farming (9.1%) and cane rat farming (3.0%). Photo 1, 2 and 3 illustrate some of the alternative income generating activities carried out by community members that have been introduced and promoted by the Government and NGOs agencies to conserve the environment and improve on the livelihoods of the communities.

Figure 3. Alternatives income generating activities carried out by the communities sampled

Source: Fieldwork (2018)

Community Belief System

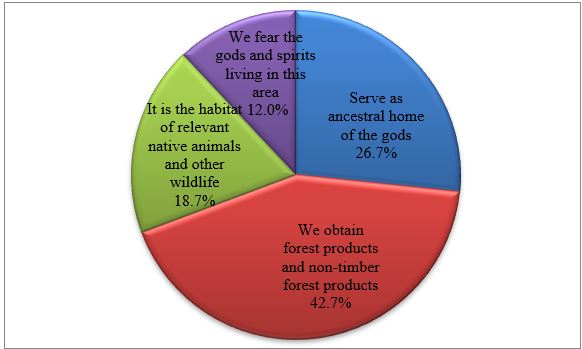

Statistically, there was substantial evidence that native beliefs are integral to forest resources in the Mount Cameroon Forest Reserve as was asserted by 115 (70.6%) of respondents. Several gods were associated with this; namely, Epasa Moto, Maley (Njoku) and Nganya. Rituals included libation to the gods of the forest and the local communities believe have a responsibility to protect the forest. It is believed that these gods live in the resources, heal the land and protect the people. All these beliefs contribute to traditional forest conservation. Equally, 63 (38.2%) participants noted that they practised traditional forest conservation by swearing to the gods and by creating sacred forests. Other forms of conservation employed by community members include owning a farm, keeping a garden, educating community members, protecting and or planting trees, keeping a natural environment, and respecting conservation rules and laws.

Community members protect the forests mainly because it is where they obtain forest products and Non-Timber Forest Products (42.7%), it serves as ancestral home for the gods (26.7%), it is the habitat for relevant native animals and other wildlife (18.7%), and because they fear the gods and spirits living in the forest (12.0%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Reasons why community members protect the forest (N=165)

The mystical attributes of specific forest resources often play a crucial role in traditional healing practices. Forest products are used in healing throughout Cameroon and West Africa, depending on the mystical values associated with the different forest species. Also, forest foods are featured in cultural ceremonies including marriage, funerals, initiation, installation of chiefs, and birth celebrations. Palm wine and cola nuts are important symbolic foods throughout humid West Africa. The forest area has a symbolic and mystical power (Epasa Moto) valued by the Bakweris of South West Cameroon. The “temple” (the site of initiation ceremonies and rites) is always situated at the foot of a large forest tree where medicinal plants are often cultivated. This tree symbolizes the forest which houses the body of the god and was once the source of people’s food. Therefore, traditional belief in general is related to the forest, as the Bakweris hold the belief that the forest serves as a home for their ancestors and the gods. Religiously speaking, the forest is a centre for ritual sacrifices, offerings and pouring of traditional libation to the gods of the Mountain.

Socially, the forest acts as an abode for some cultural symbols and animals like the elephant (Njoku). Cultural artifacts are also derived from the forest to portray and preserve the culture of the people. The forest also serves as a centre for traditional rituals and sacrifices, offerings and pouring of libation to the ancestors that they believe live in the forest, heal the land, protect the people and live in the resources. Also, the forest to the people is used for ancestral consultation to commune with the gods for the development, blessing and liberation of any curse befalling the community[1].

Management strategies

The management of forest resources in the various communities neighbouring the forest reserve is regulated by the community councils. The various councils have set standards for the kind of activities to be carried out in the forest by the communities adjacent these forest areas.

Council Management Regulations

Forbidden Activities

- Farming

- Human settlement

- Unauthorized timber exploitation

- Bush fires

Acceptable Activities

- Production and harvesting of honey

- Traditional hunting for subsistence

Management of the forest according to standards set by the councils must be participatory, with the involvement of all stakeholders, especially the local communities. The management of the forest is guided by a Management Plan that was jointly prepared by all stakeholders that took into consideration the needs of the local communities neighbouring the forest reserve[2].

Main Management Institutions of the Forest

- Community Forest Management Committee

- Council Forest Management Committee

- Regional Delegation for Forestry and Wildlife Buea (MINFOF)

- Non-Governmental Organizations

Control of Activities

This is done by MINFOF through its local services like Chiefs of Posts, Divisional Delegation among others.

Expected Use of Revenue:

Revenue from exploitation is used for development purposes in the various communities neighbouring the forest reserve, the Subdivisions and the Division at large.

Legal Strategies

A significant proportion of the community members are aware of the Cameroon 1994 Forestry Laws as indicated by 137 (83.0%). The majority of those aware of the laws also comply with their proposition equal to 120 (90.0%). The absolute proportion of the community members that comply with the laws was 120 (72.7%).

Capacity Building

Only 49 (29.7%) community members were noted to have attended seminars on forest issues, which is not enough to enhance awareness in the conservation of the forests. In addition, only 34.7% of community members attended the last seminars that were organized. The seminars were mostly organized by the German Technical Cooperation (GIZ). However, many other organizations equally contributed (Table 1).

Through these training seminars, a good number of alternative income generating activities were introduced to communities by NGOs including bee farming, livestock farming, ecotourism, snail farming and cane rat farming. As observed from field work, 117 (70.9%) of the respondents noted that their communities have benefited from such initiatives and 112 (67.9%) believed they have impacted life or well-being in the communities.

| Seminar organizers | Respondents who attended seminars |

| BCN | 1 |

| COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATION | 1 |

| EruDeF | 1 |

| GIZ | 11 |

| GIZ & MCNP | 3 |

| GIZ &MountCEO | 2 |

| Green Cameroon | 1 |

| LCM Tours | 2 |

| Limbe Wildlife Centre | 1 |

| MCFMC | 1 |

| MCNP | 7 |

| MCNP, MINFOF | 1 |

| MINFOF | 6 |

| MINFOF, GIZ, MCNP | 1 |

| Ministry of tourism | 1 |

| MOCAP | 1 |

| Mt CEO | 4 |

| Mt. CEO, EruDeF | 1 |

| Mt CEO/MCNP | 1 |

| PSMNR-SWR | 1 |

Table 1. Organizers of training seminars for forest management in the study area

Source: Regional delegation for forestry and wildlife, Buea (2017)

NGOs Participation

According to field respondents, NGOs interventions significantly influence the management of forest resources, and this is done through financial support, provision of material like wheel barrows, cutlasses, hoes, pipes to connect community water, school equipment, building materials for community halls and other constructions, scholarships, and capacity building through alternative income generating activities. Some of these NGOs that played a great participatory role in forest management include:

The Mt. Cameroon Ecotourism Organization (Mt.CEO) was established with created with the following objectives:

- Transform hunters into guides and porters

- Identify illegal exploiters of the forest

- Assign guides and porters to take tourists up the mountain

- Organize trips to Mt. Cameroon and around the Subdivision

- Sensitize and educate local communities on forest management through ecotourism

- Identify and institute alternative livelihood projects in local communities.

Mt. CEO has introduced some of the activities to the local communities they work with in order to divert focus on forest exploitation to forest conservation. This is possible through the introduction of income-generating activities like ecotourism, mushroom cultivation and provide support to community agricultural projects like yams, plantains, and other Non-Timber Forest Products cultivation. Communities of practice include Bova, Bokwango, Likoko-Membea, Bonakanda, and Muea. Services provide enormous support to the local communities in conserving the environment, alleviating poverty and enhancing self-employment in Buea Subdivision by identifying and transforming hunters into potters, guides, guards and patrols for Mt. Cameroon forest. These efforts respond to the need for an inclusive approach to forest management.

Pro Climate International, a Non-Governmental Organization based in Buea Subdivision, has introduced community livelihood activities. Impacts have benefited the communities in and around the Buea Subdivision. They transform hunters and illegal timber exploiters into porters and guides for mountain tours which is an income-generating activity for the youths involved. They supplied high-efficiency cooking stoves for the communities around the mountain slopes to reduce forest wood consumption and indoor air pollution. They also organize activities to help the population manage the forest resources by alleviate poverty and improve living standards through self-employment including:

- Trekking tours in the forests

- Community-based tourism activities

- The “Wonderful Bag” project to reduce indoor biodegradable waste

- Health awareness projects including basketball programs in schools.

Collaborative Management

Community involvement in the management was satisfactory with only 98 (59.4%) of the participants agreeing. Collaborative management improves consultation as requested by 78.6% of the respondents. While 155 (93.9%) of surveyed members of the communities involved in ecotourism activities, they received very little benefits from stakeholders. Only 33 (20.6%) agreed that the benefit in terms of financial and other material resources were shared, but instead reserved only for the indigenes of Bakweri. This process of benefit sharing was observed not to favour forest conservation initiatives. As reported by field respondents, only “indigenous Bakweris” community members benefit from such royalties. These come in the form of financial and material support from either the government or international organizations. This is in line with studies carried out by Tamasang (2019), who noted that the global benefits that generated from forest conservation initiatives determine the success of forest-based efforts to mitigate climate change ensure the sustainable management of the forests. Tamasang (2019) goes on to explain the process of benefit sharing in Cameroon is unfair and inequitable. The meagre percentage allocated to the local populations whose livelihoods depend on the forest is a result of unfair procedures for the transmission of the royalties to the local communities. Lack of public consultation by local councils and the exclusive management are conducive to corruption.

The local communities signature Conservation Development Agreements with Park Service is instrumental in the active collaboration of protection and management in Parks, alongside the development in agriculture and infrastructure. As stipulated by the 1994 forestry laws in Cameroon, 60 eco-guards, potters and mountain guides work in the protected areas to ensure forest resource management. The community’s development of joint controls (control involving MINEF and wildlife management committees) include tracking illegal poachers as it still remains a problem in areas. Joint control operations have succeeded in reducing poaching and even stopping it in communities. Invitation to plan and participate in prevention include:

- Park boundary opening

- Wildlife monitoring

- Joint Patrols

- Inventories for non-timber products such as Prunus which are carried out jointly by the community members together with the Mt. Cameroon National Park[3].

The success of initiative can be measured by communities around the slope of Mt. Cameroon whose livelihood depends solely on the forest being given adequate consideration by these laws. This was a concern with 1981 Forestry Law which excluded Community Forest Participation. On the 20th of January 1994, the law was revised creating Forestry law No. 94/1, 1994 which partnered the Participatory Forest Management with Local Communities to manage biodiversity and conservation of their community forest and Mt. Cameroon forest. On the other hand, the Mt. Cameroon National Park adopted a Collaborative Management Approach in line with the vision of the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife. These following responsibilities ensure the preservation, conservation and sustainability of the Mt. Cameroon fragile ecosystem:

- Facilitate the organization and functioning of Village forest Management Committees

- Facilitate the organization and functioning of Cluster Platforms to participate in the planning, implementation and monitoring of park management activities

- Support the elaboration of Conservation Development Agreement and implementation of agreed measures[4].

It was observed that community forests identified in Bwiteva and Bojongo are managed by the traditional authorities and other community leaders.

Community Outreach and Education

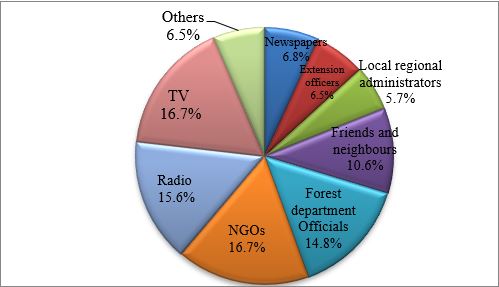

Community members are generally sensitized through the television, NGO, radio, forest officials among other media outlets (figure 4).

Figure 4. Sources of information on forest management (N= 165)

Figure 4 indicates that 16.7% of the respondents got the conservation policies from NGOs and the TV, 15.6% from the radio, 14.8% from forest department officers, 10.6% from friends and neighbours, 6.8% from newspapers while the remaining 6.5% got it from extension officers, local regional administrators and other sources not listed in the survey.

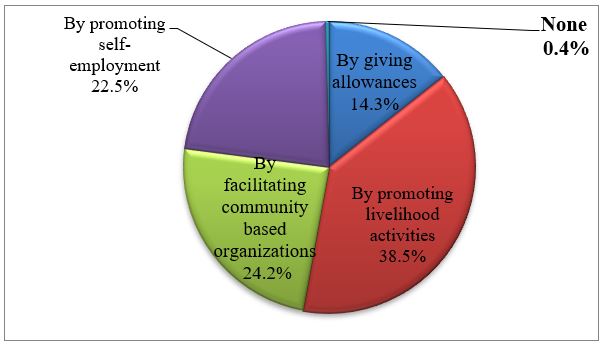

Government Management Strategies

Other strategies used by Government to manage the forest include promoting livelihood activities (38.5%), facilitating community-based organization (24.2%), promoting self-employment (22.5%) and giving allowances (14.3%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Strategies to enhance forest management (N=165)

Government and NGOs used these strategies to conserve biodiversity by alleviating poverty 98 (36.3%), conserving the environment 99 (36.7%), enhancing self-employment 41 (15.2%), and improving standards of living 32 (11.9%). Community members were generally not very satisfied with these strategies as only 66 (40.0%) assessed them to be adequate. The local populations consider NGOs as important partners as they are generally very hospitable to them 144 (89.4%). Community members collaborate with Government and NGOs in several ways including: assisting in the activities, attending sensitization meetings and seminars, conserving the environment by planting trees or keeping a small forest in one’s land, educating household members and other members of the community, going for exploitation permit, checking poaching and serving as a volunteer for NGOs. As for those who did not participate, the reasons were: they had never met with the stakeholders, they found it difficult to answer questions asked through a questionnaire during seminars or surveys, they were not aware of the management policies or were not interested, they were never contacted, they lacked finances, and absence of awareness. The dominant reason was a disagreement with the policies instituted.

Management Stakeholders

This section specially looks at the main government institutions and NGOs charged with Mt. Cameroon forest ecosystem management. Namely, the Forest Department of the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife, the Mt. Cameroon National Park (MCNP), Community Village Management Committees and other private NGOs in the Buea Subdivision. The mandates of these institutions are reviewed in terms of their interaction with communities neighbouring the forest. There are four major groups of stakeholders in the use and management of the Mt. Cameroon forest reserve area. This includes the users, Government, Development Agents, and other private groups. The users, often communities nearer to the forest of Mt. Cameroon, represent the most complex group as they are the ones most affected by the resource management decisions. They rarely form a homogenous group because of the diverse range of interests and characteristics that exist among them. Differentiation in their participation can be based on age, gender, education, residential location and ethnicity.

The government may include both the government with sovereignty over specific natural resources, and other external governments that have a variety of regional or international interests in this resource with a desire to influence outcomes. The government is an important stakeholder because everybody else concerned with resource management has to work with or through it to some degree. Government officials in different ministerial departments, local government and other government bodies direct efforts for implementing policies and have substantial impact over current and prospective initiatives in each location. These agencies can influence policies and the way the policies are interpreted and implemented. Government’s field personnel provide a direct link between government requirements, the needs and interests of stakeholders absent from the local scene and the needs and priorities of local stakeholders.

Development agents, on the other hand, provide funds and other services to national development programs. These may include international donor organizations that grant or lend money, consultants hired to formulate, review, study and or evaluate development programs, and non-government personnel of projects funded by international donors. The non-profit private organization interests are to execute policies, remain competitive and use resources effectively, promote human or ecosystem well-being and capacity for self-help, enhance reputation and image, and improve membership or funding base.

For the purpose of this study, two government bodies, the Forest Department and the Mt. Cameroon Wildlife Department, were evaluated . This was done in terms of their role in Mt. Cameroon forest resource management and how they linked with communities adjacent to the forest in their roles.

The Forest Department (MINFOF)

The forest department is responsible for the protection and management of Mt. Cameroon forest as well as a few other forests. There management has been agreed upon by the owners, usually the councils. Implementation responsibility is vested in the forester in-charge of forest stations in the division in co-ordination with the Regional Forestry Office. The foresters’ in-charge of stations undertakes conservation and management measures in conformity with the forest conservation, which is in accordance with the forest policy of 1994[5].

Discussion of results

Results of the study reveal that, among the 165 respondents sampled who use the forest resources or products for livelihood, 43.0% earn less than 30000FCFA, 40.6% 30000-100000 FCFA and only 16.4% earn above 100,000 FCFA. The income is relatively low and indicates the poverty level of the respondents. A few factors account for this situation. German colonial rule expropriated vast lands from the Bakweris for plantation agriculture. The fertile, volcanic soils around Mt. Cameroon proved suitable for large-scale plantation agriculture, especially for crops like banana, rubber, tea, coffee, cocoa and palms. More than 100,000 ha of Bakweri land was thus expropriated. In 1964 these lands were leased by the British Trust Authority to the then newly created CDC. This act led to the loss of the Bakweri ancestral lands (Ardener, 1996). Bakweri chiefs felt betrayed and even angered as they were totally ignored in the deal. The original occupants of the lands (the Bakweris), were expelled and sent to restrictive native reserves as German companies rushed to the area in a bid to get the best tracts of land (Konings, 1993). In protest, the Bakweris showed little enthusiasm in working on the plantations; at least not for menial jobs as semi-slave labourers in the plantations, and on their native land which was seized. They saw it as double exploitation by the Germans. Therefore, German planters were compelled to recruit labour from other areas in and out of Cameroon, like the North West and Western Regions and other parts of West Africa like Nigeria (Konings, 2001). The “graffi labourers” from the North-West Region found a place of safety in the fertile coastal land and with their honesty and ingenuity, worked doubly hard not only for the money but for the acquisition of lands in return. In the course of labouring in the plantations, they gradually sneaked in their wives and children from the highlands to join them in the plantations and in this way started their family expansion, occupied lands in Fako Division and later outnumbered the few and lazy Bakweris (as referred to by the German Planters) who had refused working on the plantations. With this, the drama of the North-West population pouring into the South West Region and Buea Subdivision in particular was already set (Ngwane 2012). This pressure has aggravated the Bakweri land crisis in Fako Division and has left the natives with little or no land for subsistence farming. This is why the people turn to the Mt. Cameroon Forest for their livelihood. The community members also complain of high unemployment rate and inadequate road networks linking the rural areas to the urban centres to market their farm products. As a consequence of such barriers, poverty has become the order of the day. According to the World Bank Development (WDB) Report (1992), the poor are both victims and agents of environmental damage. Not only do they suffer from environmental degradation, they also contribute to degradation because they are forced to live in ecologically fragile zones. Also, they lack the resources, property rights and access to credit necessary for investing in long-term environmental protection. Since the poor are less likely to “escape” environmental problems, they also benefit the most from environmental improvements. The WDB research in support of 1992 report, further stressed that many of the environmental problems faced by developing countries such as unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, soil depletion and indoor pollution from soot and smoke are closely related to poverty with significant implications on climate change.

Findings further show that the percentage of highest level of schooling attained by respondents in the four communities sampled cumulatively reveal that 55.8% of the respondents had attained secondary education and only 20.6% had attained primary level, while 3.0% had never been to school. As outlined by the UN Agenda 21, environmental education and awareness are important components of any viable strategy to improve environmental information and to confront issues such as deforestation, desertification, and loss of biodiversity, air and water pollution. Countries must recognize the need to tailor environmental education to all levels. Curriculum in primary, secondary schools and higher learning institutions and in the non-formal sector help build citizens’ awareness of environmental concerns and reinforce protection measures which are essential for climate change mitigation.

Findings equally revealed that malaria is the major health problem faced 61.2% of the community members. However, ill health is linked to poverty and environmental degradation. The absence of reliable and affordable healthcare has caused a high proportion of the population, especially members of the local community to rely on medicinal plants for health. Population pressure on a fragile resource base for medicinal purposes like Prunus African in the Mt. Cameroon forest area in Buea Subdivision has resulted in environmental degradation. The continued reliance of the local populations on traditional medicines is partly attributable to the economic situation of communities that are not serviced by modern health facilities, services and pharmaceuticals. Medicinal plants are of critical importance especially in poor communities due to the fact that even cheap western medicines remain prohibitively expensive. But in many cases, this problem is also attributable to the widespread and deeply anchored belief in the effectiveness of traditional therapies. Despite the efforts of NGOs and Government in conserving the forest resources for sustainability, the local people still ignore efforts that inhibit programs of climate change mitigation.

Research also indicates that the target population was relatively young, with (53.3%) of them aged between 15-30 years, 18.5% between 31-45 years and 18.2% aged 46 years and above. The most active population are those who illegally exploit forest resources for their livelihood and income-generating activities. They are the most vulnerable and must be educated on the need to respect existing forestry policies. Also, sustainable youth employment will curb the high rate of youth unemployment. This would ensure that communities adjacent to the forest are less dependent on the forest resources for their livelihood.

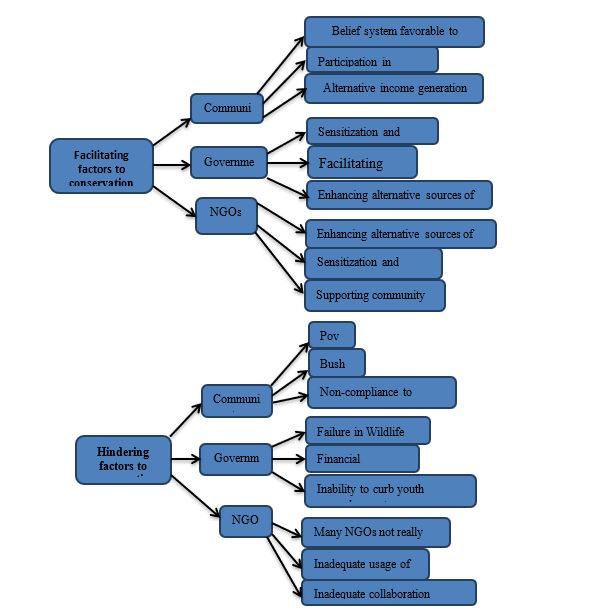

Figure 7. Facilitating and Hindering factors for the management of Mount Cameroon Forest Reserve

Source: Authors conception

Conclusion and recommendations

This paper provides an in-depth analysis of the participatory management of forest resources in communities adjacent the Mount Cameroon Forest Reserve, located in the Buea Subdivision of the South West Region of Cameroon. It has been observed that despite numerous conservation and management initiatives implemented by major stakeholders to ensure sustainability, the forest still suffers from illegal exploitation by the local populations. This study identifies various barriers to the efforts of conservation initiatives. As noted by Nana (2007), achieving sustainable forest management in Buea Subdivision relies on the capacity to address in an integrated manner, major environmental issues that include the choice of governance systems and policies, population management system, and the choice of technology and education. The cost effectiveness of such integrated policies requires the ability to consider the policy linkages between environmental, social, economic and ecological components of the communities concern. With the communities neighbouring the forest reserve high dependence of major products and services, future prospects remain high that no promising haven for some of the forest species, especially those in high demand in the neighbouring markets in Buea. According to studies by Desloges (1998), participatory forest resource management creates an environment in which all major stakeholders collaboratively plan and act together. This is important to establish how the resources should be used for the benefit of all partners, including future generations. Therefore, the need to share power with all stakeholders and the local communities help evolving procedures appreciated by all participants in the development, implementation and management policies. This is critical for sustainable forest management. Without these effective mechanisms and strategies to ensure local participation and equitable benefits sharing of forest royalties, development and implementation decisions will not be able to address the object of their creation.

It is therefore recommended that the capacity of local communities adjacent the forest reserve is developed to accommodate broader forests management schemes. The benefits accruing from the management of other forest resources must support, with priority, the livelihood conditions of the local communities neighbouring the forest. A legal framework that addresses the issue of benefit sharing must be formulated to take into consideration the needs of all in order to ensure recommendations are effectively implemented. It is important that income-generating activities are effectively introduced and encouraged to augment earnings of hunters and those involved in wildlife management. Finally, education of the population on the benefits of improved land use management must prioritize for long-term sustainability and climate change mitigation.

References

Besong, John, Ngwasiri, Clement Nforsi. 1995. The 1994 Forestry Law and Rational Natural Resources Management in Cameroon. Yaoundé: PVO-NGO/NRM.

Desloges, Claude. 1998. Community Forestry and Forest Resource Conflicts – An Overview. In Integrating Conflict Management Considerations into National Policy Frameworks (p. 31-51), Proceedings of a Satelite Meeting to the XI World Forestry Congress, 10-13 October 1997, Antalya, Turkey.

Ekane, Nelson Beti. 2000. The Socio Economic Impact of Prunus Africana Management in the Mount Cameroon Region. Case study of the Bokwango Community. Presented as partial fulfilment of the degree of M. Sc. From the department of Urban Planning and Environment, Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm.

Food and Agricultural Organisation. 1995. Report of the international expert consultation on NWFPs, Yoghuakarta, Indonesia, 17-27 January 1995. Rome: FAO, NWFP.

Food and Agricultural Organisation. 2001a. How forest can reduce poverty. Rome: FAO.

Food and Agricultural Organisation. 2001b. State of the world’s forest. Rome: FAO.

Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (GESP). 2010. Reference Framework for Government Action over the period 2010-2020.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 1994. Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories. IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas with Assistance of the World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 2006. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Rreport.

Lambi Cornelius Mbifung and Oben Timothy Mbuagbo. 2003. Some aspects of intra community land conflict in the Mount Cameroon region. Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 3 (1), 67-80.

Lambi Cornelius Mbifung. 2001. Environmental Constraints and Indigenous Agricultural Intensification in Ndop Plain, Upper Nun Valley of Cameroon. In Readings in Geography. Bamenda: Unique Printers.

Mbarga Owona, Daniel. 2019. Indigenous people and climate change in Cameroon. In Patricia Kamari-Mbote, Alexander Paterson, Oliver C. Rupple, Bibobra Bello Orubebe, Emmanuel C. Kam Yogo (eds.), Law, Environment, Africa. Publication of the 5th symposium/4th Scientific conference/2018 of the Association of Environmental Law Lecturers from African universities in coorperation with the Climate Policy and Energy Security Programme for Sub-Saharan Africa of the Konrade-Adenauer-Stiftung and UN Environment.

Mboh, Hebert. 2001. Vegetation assessment of Takamanda forest reserve and comparison with Campo Ma’an and Ejagham forest reserves. Memoire dissertation, University of Dschang.

Mouangue Bonam Kobila, Gabriel James. 2009. La protection des minorités et des peuples authochtones au Cameroun. Entre reconnaissance interne consacrée et consécration universelle réaffirmée. Paris: Dianoïa.

Mvo, Clerkson Wanie, Ebai Enow Oben, Emmanuel, Molombe Jeff Mbella and Tassah Ivo Tawe 2017. Youth Advocacy for Efficient Hostel Management and Affordable University Students’ Housing in Buea, Cameroon. Emerald International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 10 (1), 81-111.

Nana, Celestin. 2007. Wetland Management for the Conservation of Water and Biologic Diversity for Sustainable Development: measures and Strategies to Mitigate the Degradation of Wetlands and Related Consequences. CADI/GOOAHEAD, 3, 2-3.

Ngwasiri, Clement Nforsi 2001. European Legacy on Land Legislation in Cameroon. In C. M. Lambi, E. B. Eze (eds.), Readings in Geography (p. 341-348). Bamenda: Unique Printers.

Okafor, Jonathan Chukuemeka. 1998. The use of farmer knowledge in NWFP research. Sour, 1994 sustainable chances of NTF resource World Bank technical for the World Bank. Washington.

Tamasang Christopher Funwi. 2019. Forests, Forest rights, benefits-sharing and climate change implications under Cameroonian law. In Patricia Kamari-Mbote, Alexander Paterson, Oliver C. Rupple, Bibobra Bello Orubebe, Emmanuel C. Kam Yogo (eds.), Law, Environment, Africa. Publication of the 5th symposium/4th Scientific conference/2018 of the Association of Environmental Law Lecturers from African universities in coorperation with the Climate Policy and Energy Security Programme for Sub-Saharan Africa of the Konrade-Adenauer-Stiftung and UN Environment.

Tassah, Ivo Tawe. 2018. Highlands Vulnerability to Cattle Rearing in Momo Division, North West Cameroon. Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, 3 (1), 10-15. Doi: 10.11648/j.larp.20180301.12